Wolfwalkers: the Story behind Story

I moved to Ireland on June 4th, 2017, shortly after an ephemeral studio job in Madrid. I had just been hired by Cartoon Saloon—the indie darlings behind The Secret of Kells—following a string of disappointing experiences navigating the studio system. Truth is, I’ve always felt out of place in the animation industry. In my mind, movies are movies, and Perfect Blue or The Iron Giant are not that different from Black Swan or E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. But as soon as you land in animation you notice that the powers that be push for a rather specific industry culture, and if you’re not into family-friendly comedy or social satire, you’re in for a rough ride. In my case, as someone whose idea of comedy is Fargo and who thinks of Pan’s Labyrinth if you bring up kid films, it got to a point where I started seriously considering if I would ever end up working on a project that spoke to me in any sensible way.

That is, at least, until I got the call to work on Wolfwalkers.

What will follow here is a personal account of what it was like to work on Cartoon Saloon’s story team for the duration of pre-production on that film, how it evolved from the page to the screen, and a break down of many of the choices made in order to deliver the movie’s message as effectively as possible. In total, we produced about five animatics over a period of a year and half. It was, by far, the best experience of my career to this day. I hope it makes for an interesting tale.

Summer: June to September, 2017

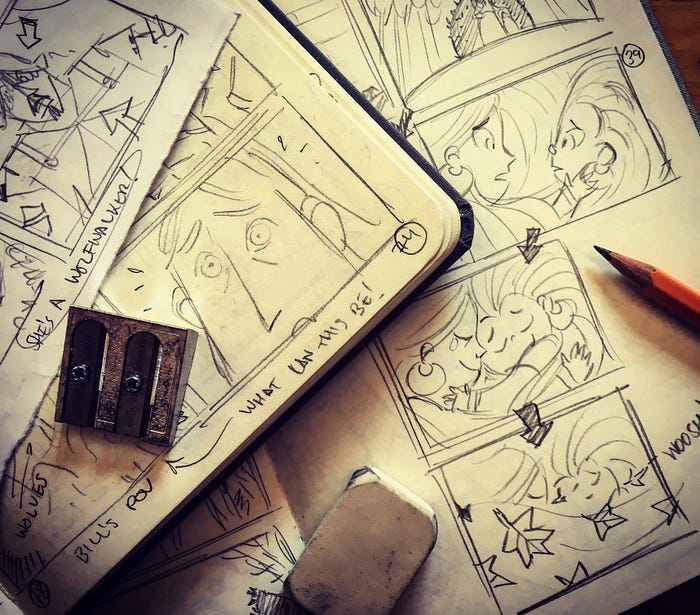

Although I wouldn’t start working until summer, I was initially contacted by line producer Katja Schumann in March 2017. This was just days before the first concept trailer for Wolfwalkers went up online, and she wanted to know if I’d be interested in testing for a storyboarding position on the movie. That, I was. And I probably did well on the test, because shortly afterward I was asked to read the screenplay by Will Collins in order to have an interview with directors Tomm Moore and Ross Stewart. I should say here that when being considered for a story position on animated movies—or TV shows for that matter — it’s highly unlikely that the candidate will ever get to read a full script. In fact, chances are that there isn’t even a full script when you start working. Wolfwalkers not only had one, it was already the fifth draft and it was rather solid. This is more or less what I told Tomm and Ross when I first met them, along with some notes on those points I found worth discussing.

That I had been given the opportunity to read a screenplay before agreeing to do the job was already odd, that the job interview itself revolved entirely around analyzing that screenplay and making sure I was fluent in story broke all records of the bizarre. Later that day, a colleague working on another film concurrently in production asked me how the interview had gone. When I mentioned that I had read and loved the script, he answered: “Wow, that’s the first time I hear a story artist in animation say that they liked a screenplay!” I suppose some of us are hard to please by nature. But it wasn’t the last thing out of the ordinary I was going to experience in the following months.

Wolfwalkers was the first Cartoon Saloon movie with a proper story team. Prior to it, there had been story artists on their films, but never as a deliberate effort to mimic the system commonly used in Hollywood. That means having a group of people translating sequences from script to animatic largely on their own and pitching them to the directors. The main difference with the traditional formula was the absence of a head of story, a supervisor of sorts that works hand in hand with the director and coordinates the rest of the team separately. Tomm and Ross did this part themselves, so everyone had direct access to them at all times. In my experience, this not only made communication a thousand times faster, it also allowed for a better understanding of the feeling the directors were trying to convey with each scene. Without the usual hierarchical order, it was simply easier to get to the crucial ‘creative alignment’ stage that a film crew needs to reach in order to deliver cohesive material, and it gave the whole process a family workshop vibe that made you feel like the project was as much your own special responsibility as it was the next person’s.

All together, the story team was comprised of Giovanna Ferrari, Guillaume Lorin, Louise Bagnall, Jez Hall, Ariel Ries, Arina Korczynski, Joe Carroll and myself. At one point, Matt Jones also joined remotely for an extra hand. And Tomm and Ross did tackle some sequence passes themselves as well. Despite all those names, people came and went, and the group remained locked at four people for the most time. Only Giovanna and I were present throughout all stages, sharing most of our workload with Jez and Guillaume for the first animatic assembly between June and October, 2017.

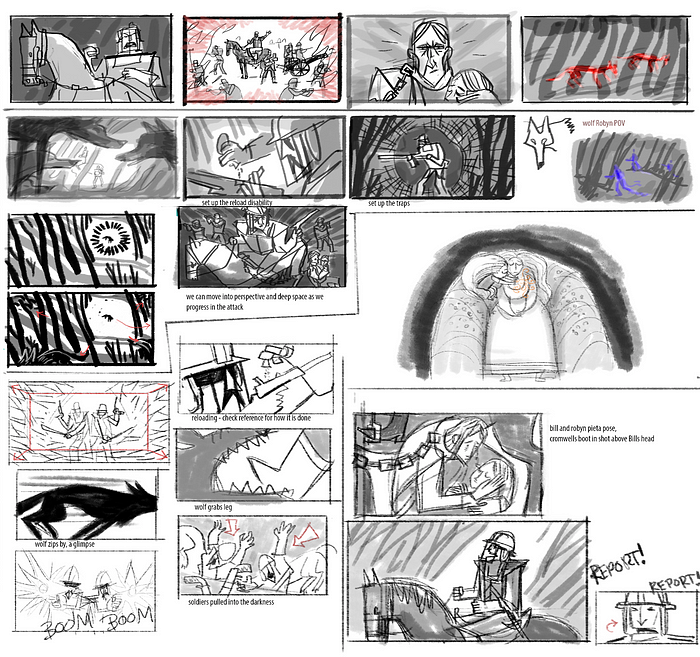

After a warm up exercise involving Robyn and Mebh spying on Bill through the magic vines, my first real pitch dealt with the scene where the girls steal food from the woodcutters’ camp. I guess this was given to me because of my past working for American studios, so the directors must have assumed I was an animation gag kind of guy. Shockingly, my idea of turning the woodcutters’ wagon into a seesaw while Mebh darted unseen from left to right was successful enough that it made it all the way to the final movie. However, this was bad news, since I was deeply aware that I may get away with a funny gag once or twice, but casting me as the visual comedy guy could only lead to disaster in the long run. In consequence, soon after I delivered the wagon sequence, I went up to Tomm and said: “Hey, you guys have, like, the Battle of the Somme going on at the end of this script, can I do some of that?”

It turns out that part of the movie had been originally saved for later in the process, and it still lacked much planning when it came to geography and pacing. What we did know is that it was going to be a big action set-piece, and no one on the team was particularly inclined toward action except for me. As a result, I was given free rein with it for a couple of weeks.

Although nobody fit a particular profile and we all ended up sharing sequences, at the beginning Gio did tend to work on emotional scenes, Guillaume was often handed quirky or dynamic ones, and I built a reputation as the action-adventure type. Considering we were making an adventure film, I guess that was a good thing. But also a challenge.

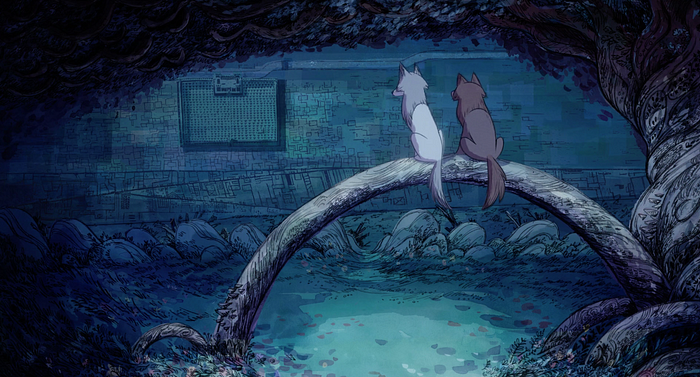

Tomm Moore is known for his almost religious devotion to flatness and his emphasis on illustrative design. If you talk to him for more than two minutes, you’ll soon learn that in the beginning, Richard Williams created the heaven and the earth, and that The Thief and the Cobbler is sacred scripture. Getting to know the many influences that shaped Cartoon Saloon since its inception was a particularly eye-opening experience, and essential to understand how the heck to even storyboard a movie like Wolfwalkers in the first place. None of us, except maybe Giovanna and Louise as studio veterans, would have known where to begin had we not been exposed to stuff like Hungarian Folktales by Marcell Jankovics and The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon by Yugo Serikawa during story briefings. Wes Anderson is another, more obvious reference, and his extremely stylized, characteristically awkward ski sequences from The Grand Budapest Hotel were screened during one meeting as visual aid for chase scenes.

“This won’t work” I remember saying. “That stuff is shot to be funny, not exciting. And your scenes here are written to be exciting.” The problem is that ‘exciting’ often requires depth, angled shots and camera movement. And every one of those things clashed directly with the visual language developed by Tomm and Ross on The Secret of Kells and Song of the Sea. It was time to develop some new vocabulary for that language, at the risk of having every action scene on Wolfwalkers fall, well, flat. But in the wrong way.

We spent the summer of 2017 mostly exploring the way the movie was supposed to look like. We fed on each others’ work and gathered as much information as possible from external influences. At this stage, everything was new. One day, while watching Gio’s take on a now-deleted scene where Robyn sneaks out of her bedroom in human form, we noticed she created an invisible split-screen by matching two different shots that resembled the profile view of a single building. When Robyn jumped out the window, she seemed to suddenly shrink as her cape, lagging in the room behind, remained normal size for a fraction of a second. “We can do that?!” was sort of the reaction the rest of us had.

I also used this time to search through the project archives in the shared team drive. Countless long-forgotten files were scattered through a myriad of folders that hadn’t been touched since long before the film’s concept trailer was made. This way I learned that Robyn had been a boy at one point, that Mebh’s mother Moll was killed and skinned in a previous version of the movie, that she eventually merged with another character meant to act as the gatekeeper of the wolfwalkers’ ravine, or that Robert Eggers’ wonderful The Witch had made such a strong impression in Tomm and Ross that they briefly considered recording the whole film in 17th century English. I unearthed some drawings by Cyril Pedrosa that made me imagine the wolf vision scenes like a mix between Three Shadows and the wraith world from The Lord of the Rings. And a handful of wolf poses by animator Aaron Blaise certainly didn’t look the way the wolves from Wolfwalkers were supposed to look like, but they were great help in order to anatomically understand them.

Although nothing was better inspiration for a film set in Kilkenny, Ireland than living in Kilkenny, Ireland while making it. I had visited the city two years before on vacation, completely unaware that one day I would end up moving there. At the time, I already knew that it was home to Cartoon Saloon, but I failed to find the studio while walking its streets. Flash-forward to 2017, and here I was, touring the city castle, stormed by Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell in 1650, shortly before he became the villain of the fictionalized account from our movie. We explored the medieval Rothe House to get a taste of how Bill and Robyn may have lived in town. And we even got to spend a rare sunny day near a waterfall at the Kilfane Glen gardens entirely by ourselves, apparently thanks to a favor that someone owed someone involving a recent visit by Prince Charles and a cup of locally made tea.

The laid-back, exploratory philosophy that Tomm and Ross adopted for pre-production worked wonders when it came to making us all feel at ease, invigorated and excited about the project, but it was a growing concern for production. Ideas were flowing and a strong bond was forming among artists, yet it was increasingly clear that we were not going to meet the deadline to have a first pass of the whole film ready before the end of the summer. On my first day, I had been told that the expectation was to have one sequence made every three days or so, with the goal of having three full animatics locked by Christmas. This sounded pretty unrealistic to me, but of course I wasn’t going to say that on my first production meeting. As time passed, this idea developed that perhaps we were wasting time going on field trips and ice cream breaks, when in reality, the final animatic would have never been done by the end of the year, field trips or not. Wolfwalkers had bigger issues than artists taking a step back to try and feel the whole picture, and everyone was about to learn that soon.

Fall: September to December, 2017

On every project developed with a story team, there is a period of growing pains, during which entire chunks of film have only been touched and interiorized by a single artist, and problems begin to pop up here and there that others may not be aware of. These tend to be specific, although Wolfwalkers also had a bigger structural issue that had been around for a long while. Early rough cuts of the movie hinted at a strong third act, with a meandering first half of the second act and an overlong beginning. There was also some muddy thematic messaging, which troubled me in particular. The movie seemed to be about Robyn’s desire to live free of the city’s constraints, while also describing an arc that had her go from hunter-wannabe to animal rights activist. Guillaume started noticing inconsistencies in her character. Gio, in turn, was worried about Bill and Cromwell’s journey. Jez left the project once the first animatic was completed, and was later replaced by Louise. He never knew, but I secretly took a stack of drawings from his desk. The man drew just like Mike Mignola.

For a short period around this time, Ariel Ries joined the team as well. She was the first and only story intern we worked with, although calling her an intern was merely a formality. Unlike most artists-in-training, she jumped straight into boarding sequences from the start. I often say that storyboarding skills are something you develop at home, mostly fueled by personal interest, and Ariel had a great eye for detail and genius to spare. If you catch Wolf Robyn shaking herself dry over her own human body shortly after her close encounter with Cromwell, that was Ariel. So were beats of Bill tracking down Mebh in the forest and the aftermath of the big run from the cave.

As her internship drew to a close, Ariel gifted Tomm and Ross with a mock-up Wolfwalkers poster that parodied Renato Casaro’s original 1982 one-sheet for Conan the Barbarian. I remember asking Federico Pirovano, a former classmate of hers, whether it was normal for students in Denmark’s The Animation Workshop to be fans of such movies in this day and age. It turns out Fede himself was also a major Conan fan, and would end up becoming another key member of our team as a character designer. Regardless of their high fantasy leanings, The Animation Workshop must give something to their students in their lunch menus that other art schools are missing. If it wasn’t for their constant influx of talent, Wolfwalkers would have not been the same.

Although ‘same’ is the last thing the project could have been, especially considering its gradual transformation since the very first days. Studios are often secretive about early drafts and cuts of their movies, sometimes keeping them away even from the crew working on the project itself, but knowing what came before is paramount when it comes to story. It allows you to understand why certain choices were made and if the twists and turns taken are actually leading you to where the directors expect to arrive. In the case of our film, Act 1 was perhaps the most telling out of all segments in the narrative, because it summarized several shortcomings fairly well.

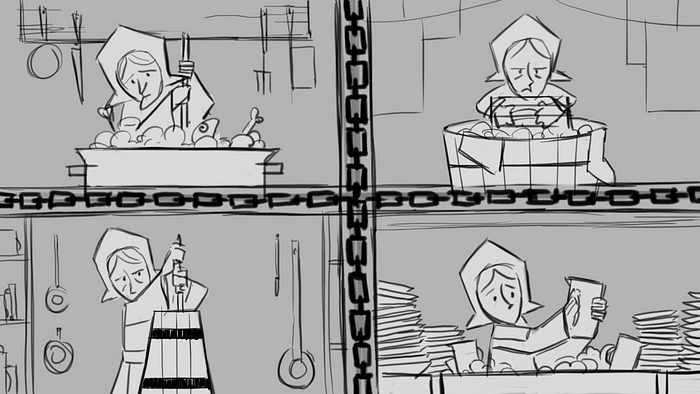

Once upon a time, Wolfwalkers opened with a narration over a wolf vision sequence depicting an attack on sheep. From there it cut to Bill and Robyn living off the woods near Kilkenny, Bill being a hunter that shared a troubled past with Cromwell, and Robyn as a ditzy kid that cherished the outdoors and dreamed of mermaids and dragons. However, the forest is a dangerous place filled with wolves, so Bill wanted to offer Cromwell his services as a hunter in exchange for a pardon and a safe home to raise his child. Eventually, father and daughter met with the evil Lord Protector and a deal was reached. Robyn was put to work as a scullery maid in Kilkenny Castle while Bill went off on hunting trips. Disappointed and eager to return to the woodland, Robyn would then sneak out of the city determined to hunt a wolf and prove she can handle herself in the wild.

First of all, it seemed odd to introduce Robyn as this nature lover enchanted with birds and trees, only to have her obsessed with the idea of killing a wolf as a way to secure her place back among the animals. Bill and Cromwell’s backstory was pretty interesting, but it slowed down a first act that already took long enough to reach the inciting incident of Robyn being accidentally bitten by Wolf Mebh. The earliest victims of these conclusions were a sequence of Bill and Robyn sharing a moment in the forest together and an ever-changing scene in the castle’s throne room where Bill pleaded his case while the Lord Protector established the film’s lore by downplaying farmer stories about the wolfwalkers.

The need to introduce the internal logic of the wolfwalkers was explored in different ways for while, including making Robyn aware of their existence from the start, Cromwell mentioning them, and even through an intro montage with St. Patrick blessing the wolves of Ossory and the origins of the pagan wolf people explained. Although personally I didn’t like any, I was especially opposed to this last option, as it meant creating what I refer to as an ‘instruction manual sequence’. These are common in animation and basically spell out the film’s backstory for the audience in a lazy and inorganic way. One evening after having worked late, I found myself alone with Tomm at the studio. We started talking about the movie’s plot, and I said “You know, so far you guys have had everyone in this movie talk about the wolfwalkers except for the one person who would be spreading stories about them like crazy: that dude who’s complaining about wolf attacks to the English soldiers early on.” This character would later become Sean Og, played by Tommy Tiernan, and this suggestion informed the idea of having him be the witness of a wolfwalker encounter in a future reworking of the prologue.

Other problematic bits included Robyn and Mebh’s first meeting at the forest clearing, their confrontation prior to the castle courtyard sequence, the intricacies of Cromwell’s plan to eradicate the wolves, and the night scene where Wolf Robyn and Wolf Mebh open up to each other while looking at Kilkenny from an oak tree. This last thing represented a narrative midpoint of sorts, and it had been a personal thorn in my side ever since I first read the script. Originally, the story made Mebh aware of Moll’s whereabouts in Kilkenny, the problem being that she couldn’t track her all the way to a precise location in wolf shape because entering the city as anything other than a human meant certain death. She used to tell Robyn this much, but Robyn wouldn’t put two and two together and tell her new friend that the Lord Protector kept a conspicuously large cage in his trophy room that could hold nothing but the wild girl’s lost mother.

Now, it must be pointed out that despite these hiccups, screenwriter Will Collins still did an amazing job. Wolfwalkers is the best written animated movie I have worked on by a long mile, and I would even go as far as saying Will’s script is the main reason why it’s a good film to begin with. That is often the case with any movie, and animation is no exception. Different departments can elevate the work of those who came before in the production chain, but without a solid foundation, no amount of beautiful art can save a film. One advantage that animation has over live-action is that a story team can help iron out kinks in the screenplay to further cement that foundation. Depending on the degree of freedom entrusted to them, story artists can exhibit qualities from both directors and writers. Truth is, they can be something like a cross between a second unit director and a script doctor. In Wolfwalkers, this ended up being quite literal.

“I don’t want you to work on something you don’t believe in,” Tomm told me once. I don’t think he realized how surreal that sounded to me at the time, but a director telling you that was pretty darn unprecedented in my experience. The reason he was saying it was because the night scene with Wolf Mebh and Wolf Robyn that I described earlier had just been assigned to me, and I just didn’t buy what was on the page. “Go home and write it however you like, and we’ll see,” he said next. So off I went, I rewrote the dialogue and brought it to the studio the next day. Tomm and Ross, in turn, rewrote my lines their own way. And then I rewrote theirs. We continued with this back and forth for a while until we were all satisfied. Since the process worked, we got to repeat it again with other scenes in the future. Today, you can hear lines here and there in the final movie that originated from some of these sessions.

Still, the movie had problems that went beyond precision rewrites of isolated sequences, and a major overhaul was needed. This largely happened over the Christmas break of 2017, and in January the following year. Wolfwalkers, as it is now, was pretty much born around those dates. But before getting there, the team lost a couple more early members that defined much of the project’s identity. Guillaume Lorin flew back to France to direct a shortfilm called Vanille, and half of Ireland cried as he set forth. He had not only been the studio’s motivational savior through sheer friendliness; his storyboards had such a lasting impact on the movie’s DNA that many survived a whole year of revisions that followed his departure. The iconic ‘running with the wolves’ music montage, for instance, was single handedly drawn by him and went straight from his pen to the animators’ hands with no other board artist ever having to tweak anything on it. The second loss we suffered was editor Darragh Byrne, a Saloon veteran of Kells and Sea fame, who shared much of Guillaume’s cheerfulness and often was the filmmaking authority in the building. I’m thankful to him for being one of the first who championed my early work on the film’s third act, and for countless talks on recent cinema releases, hot new videogames and the work of the late Johan Johansson. His role was taken over by former assistant editor Richie Cody, himself helped remotely by Darren T. Holmes.

Winter: December to March, 2018

January 2018 was defined by brainstorms, meetings and script rewrites. I spent half of my holiday break writing notes on ongoing changes, but then again, I spent half of the entire production writing notes on anything if you ask Ross Stewart. During this time, Nørlum studio director Jericca Cleland was brought in as a story consultant. I believe the New Year also marked the first time The Breadwinner director Nora Twomey watched the animatic, and noted that this was “the best Cartoon Saloon storyboards had ever looked.” Ironically, the storyboards from Wolfwalkers were quite rough in terms of drawings and never improved all that much. But that’s how you can usually tell if a story artist actually focused on what really matters.

On a side note, the release and eventual Oscar race entry of The Breadwinner had a definitive influence on the Wolfwalkers story team that the directors might not have been aware of. Back during a studio screening of Nora’s film, I remember turning to Guillaume and commenting “Well, shit, now we have to make something better than this.” He laughed and nodded. As Cartoon Saloon continued to pile up improbable Oscar nominations, there was a growing fear among creative directors of ever becoming the first one to drop the ball. Not that Academy Awards are the official confirmation of whether anyone has been an accomplished filmmaker or not, but either way they represent an honor without which an independent studio like the Saloon may have never survived past the making of The Secret of Kells.

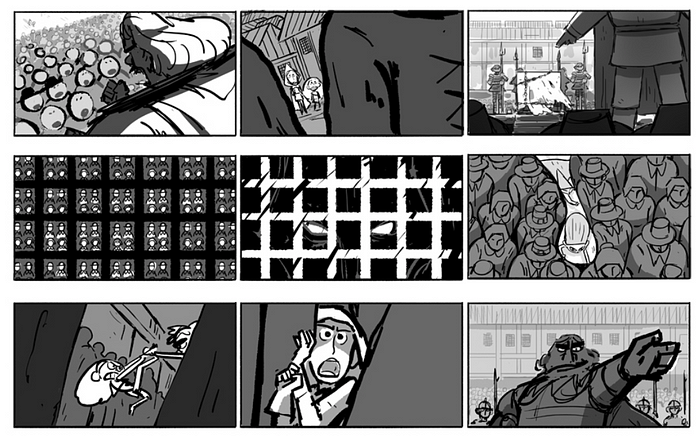

As January progressed, Wolfwalkers began to grow its figurative fangs. Several weeks of story meetings later, the film as we know it began to take shape. The first thing to go was the old Act 1, with Bill and Robyn hiding in the woods. Now Bill was going to be enlisted in the English Army from the beginning, with Robyn staying safely at home in Kilkenny. The reason she snuck out of the city wasn’t to prove she can hunt a wolf anymore, but rather because she was looking for her pet falcon Merlyn, taken by the wolfwalkers after she accidentally wounded him with her crossbow. Mebh was also no longer aware of where her mother Moll may have gone to, and the midpoint scene now focused more on her opening up about her inner fears than rationalizing what’s keeping her near the city. One final point of contention was Cromwell’s plan, as it wasn’t clear what exactly he was going to tell the townsfolk in the castle courtyard or why he was keeping Moll alive. Giovanna decided to make her last stand around this topic, and having graduated with honors in troublemaking, I of course chose to side with her.

“It just doesn’t make sense,” we said. “Why doesn’t he just kill the wolf to show the townspeople he means business?” Logic isn’t always the best storytelling companion, but something about Cromwell’s nebulous ploy with the caged Moll was bothering us. I personally insisted so much that the courtyard gathering should be laid out as an execution scene that at one point I even had a cameo in the scene, my character shouting “kill the wolf!” in the crowd. You can still find me there, but I no longer shout. Still, our arguments were compelling enough that Tomm eventually decided to give them a thought and tasked Gio and I with exploring an alternate subplot for Cromwell. There was a catch, though: whatever we came up with had to fit with the midpoint scene where the girls bonded at the oak tree as it was written. This turned out to be far too difficult to implement without fundamentally altering the heart of the movie, so a less aggressive solution was sought.

In the end, the execution set up did take place. Cromwell gave his grand speech while parading a weakened Moll before the audience as a way to symbolize his efforts to subdue the Irish. Then, all hell breaks loose the minute Mebh shows up. An earlier version of the scene I boarded had her learning from Robyn that Moll was being kept prisoner somewhere in the castle, then rushing upstairs only to find the trophy room empty. “I don’t understand, it was right there,” Robyn said. That moment, noise coming from the the courtyard revealed to a panicked Mebh that her mother had just been moved out and was likely going to be killed before a crowd, after which the sequence continued largely the same. One final detail that changed was the manner in which the town kids slowed Mebh down by caging her like a wild animal. Originally, they did this spontaneously, and then forced Robyn to prove she’s a real hunter by firing a toy crossbow on her friend. The problem here was that the beat was more about the kids’ own quarrel with Robyn than anything between Robyn and Mebh, so it lacked emotional resonance. Louise was the first one to point this out, and she suggested making Robyn actively seek the kids’ help as a way to betray Mebh’s trust.

Toward the end of winter, as the film’s final storyline became more clear, the issue of how three board artists were going to redraw an entire animatic without spending ages on it got more pressing. Production had been hoping to be done with storyboarding by New Year and things were now suddenly looking like everything just moved back to square one. Again, realistically there was nothing that could have prevented the situation, but looking for ways to speed up the process didn’t hurt either. One proposed option was to set up brainstorm meetings between Gio, Louise and I were we would thumbnail new sequences together to be later divided between us. Among the scenes that came out of these meetings were the new cold open with Sean Og facing the wolves, yet another pass on the first encounter between Robyn and Mebh, and the streets of Kilkenny during the first act.

Out of all these scenes, the revamped intro with Bill and Robyn was the one we struggled with the most, as the characters walked a fine line between having a loving father-daughter relationship yet being frustrated at each other. As the only person who really pictured it, Tomm ended up boarding that sequence. I took the wolf attack, just like I had taken all the previous wolf attacks. Gio added the quick-cut playfulness of the forest clearing scene once Robyn falls into Mebh’s trap. And Louise handled much of the early cave sequences. Overall, we managed, but as the year progressed it grew evident that we were going to need a couple more hands.

Spring: March to June, 2018

“Are you ready for Arina?” The person asking was Mike Daley, an old mentor of mine who had been part of the team behind The Incredibles 2. Arina Korczynski had interned at the Saloon back in 2017 and helped design many shot choices that Tomm and Ross used in their story briefings for each Wolfwalkers sequence. After that, she had gone to Pixar, and now she was returning to Ireland to assist on the final push to get the animatic ready for layout. Mike kept teasing her return as if I was supposed board up windows and waterproof my basement before a hurricane. The day Arina finally arrived, I understood why.

She had very strong ideas about what stuff wasn’t to her liking, and wouldn’t mince words when it came to explaining why. One discussion about the movie once turned into a verbal bar fight between me and her that I now look back to with fondness. In reality, Arina was exactly the kind of person I would have hired for a story team if tasked with recruiting artists. There’s nothing more damaging for a film than someone who just stays quiet during meetings or simply nods when the director speaks and consistently does exactly as told. Not to say that people ought to be contrarians for sport, but it’s very unlikely that every decision made by anyone will be perfect without ever leaving some room for improvement. Because of this, when story artists keep quiet, it usually means either one of two bad things: they have lost interest in the project, or they are not confident in their own skills. Arina made it clear from very early on that she had neither of those issues.

The second extra hand that joined Wolfwalkers around this time was Joe Carroll, a Kilkenny local that in many ways was the complete opposite of Arina. Soft-spoken and agreeable, he had worked with the Saloon before and directed one of the music videos that form the Cúl an Tí song collection produced in collaboration with band Kíla a couple of years earlier. He polished scenes like the Lord Protector’s second encounter with Bill and Robyn at their house door, or Mebh’s surprise visit to the scullery. I would often work with him, while Gio was paired with Arina to focus on sequences like Moll’s spirit flight back into the woods. Spring 2018 also marked the last season Louise was part of the team, as she moved on to work on Nora Twomey’s next film in the summer.

The arrival of good weather also coincided with the voice recording sessions featuring the final cast. At first, listening to their voices felt strange, but I was anticipating this. Cartoon Saloon differs from many animated feature film studios in the sense that they use scratch dialogue to aid the storyboarding process from the beginning, instead of having the artists do the voices themselves as they pitch. This is a great idea, since it allows you to stick closer to the intended acting the director is shooting for, and it also lets the artist be more conclusive when it comes to editing choices. Still, after a whole year listening to the old recordings, there’s a short period of adjustment as you get used to the new ones. Hearing Sean Bean say anything on my headphones, for example, almost invariably led to me to picturing him going “For England, James!” while kneeling before a Russian general or muttering “My brother, my captain, my king” to Aragorn on the hill of Amon Hen. Although this was admittedly more my fault than his.

Back when casting was still ongoing, Kenneth Branagh, Patrick Stewart and Ralph Fiennes were floated as potential actors for Cromwell. Assistant director Mark Mullery suggested Charles Dance at one point, an idea that I immediately got behind, although this risked turning the whole thing into an accidental Game of Thrones reunion considering Sean Bean’s involvement. To further delve into the possibility, I joked that Sophie Turner and Maisie Williams could conceivably have pulled off a believable Robyn and Mebh themselves. Tomm and Ross were keen on finding child actors to fill the girls’ shoes though. And Mebh, of course, had to be Irish. In the end, Honor Kneafsey and Eva Whittaker were awarded the roles. Maria Doyle Kennedy became Moll. As for Cromwell, Simon McBurney voiced him and truly wrangled what I personally considered a deceptively tricky role.

The Lord Protector’s influences ranged from Kevin Spacey’s Frank Underwood in House of Cards to Richard Harris’ portrayal of the man himself in Cromwell. This biopic was the version I responded the most to. Whatever was in Harris’ head when he interpreted the character, it really felt like he was secretly playing a villain within a film designed to paint him as a hero. I also loved how brazenly religious and operatic Cromwell sounded in the original Wolfwalkers screenplay, and I tried to keep that essence alive once script changes began to soften it out of fear that it might distract from the main points in the story. While working on retakes for the castle courtyard scene, I rewrote his dialogue many times, attempting to stay true to Will’s original vision for the character while also making sure that what he was saying made some sense. However, it turns out that it’s rather difficult to make a character who only makes sense in his own head sound coherent. At one point, I remember saying: “I think the only person who will be able to make this work will end up being the actor that plays the role.” The comment turned out to be premonitory, as McBurney did a fantastic job improvising better dialogue than any of us could have come up with in ten years.

Summer: June to September, 2018

The Wolfwalkers story anniversary also marked my first anniversary working for Cartoon Saloon. But things looked dramatically different from how they had looked twelve months earlier. Gone were several colleagues that had been instrumental to the movie, and production had tripled in size with the layout, posing and animation departments starting. From time to time, a few of us lamented the loss of the original family workshop atmosphere that had reigned during much of pre-production with the constant arrival of more artists, but that’s the way of things. The film had to get done eventually, and lots of people were going to be needed in order to translate our rough story sketches to finished drawings.

It is around this point that quite a bit of the process always starts to feel like a chore. With most creative decisions already made, story becomes more about adjusting poses, tweaking shot compositions and making sure there are enough transitional panels to hook up scenes. Suddenly you are less of a story artist and more of a storyboarder, so to speak. Editorial reliance on new material to fill in gaps also turns greater, but it’s less about the board artist having the freedom to explore dramatic possibilities within sequences and more about helping the editors accomplish the cut they’re trying to assemble. Sometimes, that can lead to new exciting shot configurations that you hadn’t anticipated. Other times, it can spark debates about why one particular image needs to follow another so a sequence can flow seamlessly.

One example involving this situation happened during the editing of the climatic battle between Bill and Cromwell. The sequence had a handful of key beats that could be arranged in different ways: after a big explosion, the Lord Protector marched toward the unconscious body of Wolf Robyn while Bill pleaded for her life. Bill would then turn into a wolf himself and pounce on Cromwell, the two would fight for a bit until Cromwell wounded Wolf Bill, while Merlyn the falcon tried to wake Robyn. Finally, Wolf Bill would overpower Cromwell by biting into his sword and breaking it to pieces. At one point, a close up shot showing human Bill bleeding from the wound inflicted by Cromwell on his wolf-self had to appear. This was important because it would help Cromwell understand that Bill and the wolf were one and the same. However, I thought that the shot could serve an extra purpose: by placing it before we saw that Wolf Bill had been injured, it was possible to cut to an angry head turn from him that both confirmed the injury on each body and suggested the idea that the character had been pissed off enough to gather all his remaining strength and end the fight by shattering Cromwell’s sword. Sadly, the edit turned out to be unfeasible due to additional changes in the sequence, but I still remember this as one of the last times a conversation took place between me and editing in order to figure out the minutiae of some scene.

By the end of summer, Arina, Joe and Giovanna had left the project and I suddenly found myself embodying my entire department, a lone story guy surrounded by background artists, animators, line artists and other people completely alien to my world. Some of them were good friends, yet professionally, quite removed from the stuff I had been doing for the past year. During the following months, I would sometimes walk by other people’s desks and think “Oh hey, he’s working on my shot” only to take a couple of more steps and go “Uh, she’s working on my shot too”. Any story artist could have done this. Almost every shot had been ours at one point, and now they were going to become someone else’s, until eventually everything was everybody’s.

Fall: September to December, 2018

“This will be your last extension,” Katja said. “If it were up to you and Tomm, this would go on forever.” For all of 2018, I had been living on contract extensions to the original document that predicted the storyboarding phase to last only for half of 2017. Production felt that the animatic was already tight enough that the movie could survive without story artists sticking around on the team. But there was always something else to fix, and a couple of sequences still required far more work than project managers were aware of.

Toward the end of story, the most troublesome chunk of movie ended up being the first big part to be figured out more than a year earlier: the forest battle. It turns out that the long action set-piece that Darragh and I put together all those months before had been left on the back burner while the rest of the film grew around it. We were now well over the 90+ minutes ideal running time, and stuff had to be removed somehow.

“Why do animated movies have to run for only 90 minutes anyway?” I asked. “Who comes up with those rules?” I was not advocating for an Ulysses Cut that suddenly added two more hours of material to the story, but simply trying to point out that out there in the real world, movies generally have a standard 120 minute running time. Animation is the exception. Picture any film that shares either genre or tone with Wolfwalkers, be it Ladyhawke or Willow, and they all hit the two hour mark. Even Princess Mononoke, which is animated and an obvious influence, is slightly over two hours long. As it seems, the reason why this happens has to do with the conventional comedy tone of Western animation, kids’ attention spans and theater showings. The shorter the movie is, the more times theaters can play it over the course of a day, the less likely it is that a child will get distracted, and comedies tend to work better as one hour and a half long films. There is, of course, a budgetary reason to it as well, but all factors appear to play a part. In any case, I found it counterproductive to corset the story within an arbitrary time limit unless there was a serious financial need to do so. Yet this type of discussion fell well beyond my department, so I trusted that Tomm, Ross and company would ultimately make the right choice.

In October 2018, production moved into The Maltings, the historic former brewery from where Cartoon Saloon had operated since its founding. Up until then, the studio space had been taken up by the children’s TV show Pete the Cat, so the smaller Wolfwalkers story and design crews took refuge in a rented office building elsewhere in town. For most people, this felt like a homecoming event. To me, it was a first. I lost a window view in the process, but the new environment felt cozier and much more lived in. I was only meant to spend a month or two in there, as the storyboarding stage edged the finish line once and for all. By then, I had worked on nearly every sequence in the movie, save for maybe five or six exceptions. Everything else, I had a go at it one way or another. But all nice things must come to an end.

Around the time the forest battle was rebuilt, the animatic was locked. The final running time would be 103 minutes, giving the story a bit of extra room to breathe. After this, all remaining tasks focused mostly on tiny fixes scattered all over the film: Bill keeping wolves away from Robyn shortly after Moll’s death, the somber montage of Robyn’s routine in the scullery, inserts for Mebh’s cave incantation as she fruitlessly tries to resurrect her mother. The very last scene of consequence I remember working on was the conversation between Wolf Robyn and Wolf Moll in the Lord Protector’s chamber as the castle guard moved closer. The sequence had been missing a sense of urgency that was very present in the dialogue, so I added a few shots from Moll’s angle where the audience could clearly see light from the torches seeping through a nearby door as shouts and footsteps grew louder. Described like this, these sort of choices may seem like a no brainer, but within Wolfwalkers’ flat graphic style it was always an adventure to find the correct composition.

My contract finally ended on the last week of November 2018, although I stuck around until early December before flying back home again for the holidays. During those last days, I remember being extra aware of the tweaks I was working on, and sometimes I surprised myself thinking “I guess that was the last time I drew Robyn” or “that’s my last panel of Mebh.” I believe that after two years drawing those characters hundreds of times, I got somewhat close to getting Bill and Robyn on model, however I never really learned how to draw Mebh. She was the toughest of all designs for me. But in a way, she should be the hardest one to tame. For someone who doesn’t particularly enjoy drawing as a precision exercise, it had been fun to struggle with every single one of them.

2019 and Beyond

Soon after Wolfwalkers, I continued working for Cartoon Saloon on Nora Twomey’s next movie, and then again with Tomm on Greenpeace’s shortfilm There’s a Monster in my Kitchen. This project almost served as an appendix of sorts to Wolfwalkers, as it reunited several artists from the original crew and it screened before the film in select theaters. For most of 2019 and 2020, I tried my darnedest to stay away from production in hopes to avoid seeing any final backgrounds, animations or composited shots before release, so there would still be some level of surprise when I finally watched the movie. I wasn’t always successful, but I managed to remain in the dark when it came to several important scenes.

The large scale Wolfwalkers release originally envisioned by distributors was thwarted by the COVID-19 global pandemic, and the Saloon held a socially-distanced crew screening for those of us still around Kilkenny in October 2020. While I watched the movie, I could not remove myself from the animatics I had seen a thousand times just a couple of years before. Yes, it looked lush and beautiful, but it was the same movie I remembered from back then. Every shot was there, every line, every character trait. Whenever something looked off, it felt like it had been our fault for not catching it on time in story. Some shot might be too tight, another one too short. This dialogue should have been tweaked, that transition reworked. There is something about crew screenings that seems self-congratulatory and weird. By the time the credits rolled, I could not look at the screen. I felt immensely awkward sitting in a movie theater full of people waiting excitedly for their names to show up, when in real life, that is the part when the audience gets up and leaves. In regular movie screenings, I usually am the only dummy who waits for the entire crawl to end, but with Wolfwalkers it was like looking at a mirror and finding a giant pimple flaring on your nose. My girlfriend thought it was the best Cartoon Saloon movie to date. I couldn’t even tell anymore. In the end, people like her were the film’s audience, and not any artist, editor, actor or production manager sitting in the theater that day. That is the gift and curse of working on creative projects.

Looking back, I don’t know if the Wolfwalkers experience is something I’ll get to relive someday. I’m not even sure the work we made warranted a text this long, but as one of the original witnesses of the whole process, I wanted to share the story behind the story department and fill in a gap that is so often overlooked in behind the scenes coverage of animated movies. I have chronicled much of it in the first person to give it a logbook feel, but as I wrap this up, I would like to switch point of view and look back at the whole team as the protagonists of the story. That is, the people who sat there beside me and before anyone else joined the production. Those who were there before the trees were painted, before the rivers flowed, trying to shape a motion picture that only barely moved and still wasn’t much of a picture. The animation industry calls them story artists, but in truth, they are filmmakers.

• All artwork copyright by Cartoon Saloon & Melusine Productions.